Sunapati Thangka School

Special Offer: How About A Gift Of Art This Christmas?

Artworks are a unique, inspiring gift for Christmas and we believe our collection is a perfect fit also for Buddhists and Hindu willing to celebrate this grateful event.

Artworks are a unique, inspiring gift for Christmas and we believe our collection is a perfect fit also for Buddhists and Hindu willing to celebrate this grateful event.

Choose your favorite Mask, Mandala or Thangka painting and contact us writing “gift” on your message to receive a special discount.

Love and Blessing

Sunapati Thangka School and Shop

traditionalartofnepal.com

To reach the Christmas tree on time we recommend to order your artwork for overseas delivery no later than 10th December 2014.

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

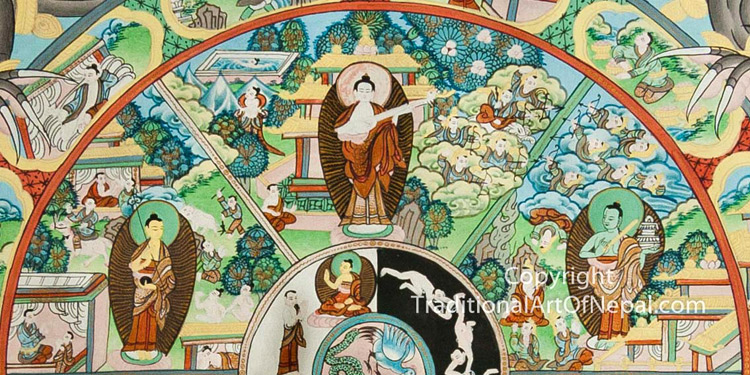

The Wheel of Life Explained

The Wheel of Life or “Bhavacakra” is well known by Buddhist monks as a powerful meditation tool and also by students to learn and understand the teachings of the Buddha. The Wheel represents the very reasons for the suffering of our mortal form, through both horrific and sublime imagery and it can be seen painted on the walls of many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in all Himalayan regions.

Essentially it is a metaphysical diagram made up of four concentric circles, held with a firm grip by Yama, the Lord of Death.

Above the wheel the sky with clouds or stars is symbol of freedom from cyclic existence or Samsara, and the Buddha pointing at it indicates that liberation is possible.

In the center of the wheel there are three animals symbols of the “Three Poisons”: ignorance (the pig), attachment (the bird) and anger (the snake).

The snake and bird are shown as coming out of the mouth of the pig, indicating that anger and attachment arise from ignorance. At the same time the snake and the bird grasp the tail of the pig, indicating that they both promote even greater ignorance.

Next to the central circle is the second layer divided in two-half circles, one light colored while the other is usually dark.

These images represent the wheel of Karma, the law of cause and effect.

The darker portion shows individuals experiencing the results of negative actions. The light half circle, instead, indicates people experiencing the results of positive actions and attaining spiritual ascension.

Beyond this layer is a wider area divided into six parts, each depicting a different realm of Samsara.

These six realms constitute all possible states of existence in the universe and all beings cycle between these states.

They can be divided into higher realms and lower realms.

The three higher realms are:

1). The Human Realm

The human realm is the world of everyday experience.

Human life, containing both pleasure and pain, makes us aware of both these aspects of life. Buddhism teaches that such harmonious balance give us the opportunity to pursue spiritual realization, this is the reason why human world is considered to be the most suitable realm for practicing the dharma.

2). The Semi-Gods Realm

The titans that live in this realm, not content with what they possess, spend their time fighting among themselves or making war to the gods.

These semi-gods do not suffer from desire or greed but from constant fighting and jealousy.

3). The Realm of the Gods

These gods are pictured like beings not so far from the human dimension in fact they share similar sensuous experiences.

The gods enjoy lives full of abundance and pleasure however they spend their existence pursuing meaningless distractions and never think to practice the dharma. This way they deplete their good Karma and they will suffer through being reborn in the lower realms.

The three lower realms are:

4). The Hell Realm

The hell is typically represented as a places of intense torment where beings endure unimaginable suffering. The victims are subjected to the most terrible tortures inflicted by demons.

In the Buddhist tradition there are eighteen “hells” that can be hot or cold.

5). The Hungry Ghosts Realm

This realm is inhabited by pathetic creatures with suffering from extreme and perpetual hunger and thirst.

They wander constantly in search of food and drink, however even if they get what they want it will cause them intense agony.

6). The Animals Realm

In this realm life is based on self-preservation. Animals live in constant fear and suffer from being attacked and eaten by other animals. Metaphor of refusal to see beyond the physical needs.

Depicted inside each realm, in some wheel of life representations, there is a Buddha or bodhisattva trying to help the beings living in that realm to find their way to nirvana.

The outermost concentric ring of the Wheel of Life present the process of cause and effect in detail.

The circle is divided into twelve parts, each depicting a phase of the law of Karma which keeps us trapped in the six realms of cyclic existence.

The twelve causal links and the correspondent allegories are:

Avidyā: Ignorance – a blind man, often walking.

Saṃskāra: Mental Formations – a potter shaping a vessel.

Vijñāna: Consciousness – a man or a monkey grasping a fruit

Nāmarūpa: Name and form – two men afloat in a boat

Ṣaḍāyatana: Six senses – a dwelling with six windows

Sparśa: Contact – two lovers kissing or entwined

Vedanā: Feeling – a men with an arrow in the eye

Tṛṣṇa: Craving – a drinker receiving drink

Upādāna: Grasping – a man or a monkey picking fruit

Bhava: Existence – a couple engaged in intercourse or a standing reflective person

Jāti: Rebirth – a woman giving birth

Jarāmaraṇa: Aging and Death – a corpse being carried

Bhavacakra Thangka paintings usually contain an inscription on the bottom explaining the process that keeps us in Samsara and how to reverse that process according to the teaching of the Buddha that said:

I have shown you the path that leads to liberation

But you should know that liberation depends upon yourself.

The Wheel of Life is also known as:

- Wheel of becoming

- Wheel of cyclic existence

- Wheel of existence

- Wheel of rebirth

- Wheel of Saṃsāra

- Wheel of suffering

- Wheel of transformation

The Himalayan Times: Sacred Nepali art losing colors

Extract from thehimalayantimes.com

Extract from thehimalayantimes.com

One of the traditions Nepal can really pride itself upon is the art of thangka paintings — which are so exquisite that foreigners have been known to extend their stay to learn the techniques. However, the rise of unhealthy competition, lack of regular-isation and emigration of artists is posing a threat to the inventive profession. Thangka is a Tibetan silk painting with embroidery, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, famous scene, or mandala. It is done on cotton canvas — found in Asian countries such as Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, India and Mongolia — used exclusively for this purpose. Native Buddhists of Kathmandu valley call it ‘pauva chitra’ whereas it is also known as ‘tangka’, ‘thanka’, or ‘tanka’.

These paintings lucidly represent Buddhist deities and divinities that appear in sacred Buddhist practices called ‘sadhana’. This means artists are not allowed to use their imagination. There is also a belief that thangka emanates positive vibrations and good luck. “Thangkas may merely seem like beautiful and luxurious showpieces for those who are unaware about Buddhist beliefs. But for Buddhists, it is a sacred tool for meditation and purification of the soul,” says Anil Ghising, general secretary of Thangka Traders Association (TTA).

The most popular thangka designs include mandala, wheels of life and life of Buddha. They can be divided into three categories according to the quality — student piece, medium piece, and master-piece. Student piece is the work of a practitioner with a year’s experience, medium piece is the work of an artist who has over five years of experience, whereas master-pieces are created by artists with over 15 years of experience in thangka painting.

This is the major reason for the difference in the prices of similar-sized thangkas. The lack of uniformity in prices also depends upon size, art, toil and materials used. The price of thangkas begins at around Rs 500 and goes up to millions of rupees.

Meanwhile, Hajar Singh Lama, president of TTA, laments about the unhealthy competition in the market. He says, “The trend of pre-set contract with tourist guides is the major reason for such competition. Tourists are compelled to buy thangkas at the store specified by the guide, which is akin to deception.” According to him, the best way to stabilise the business is to draft and implement regulations for establishing thangka shops. Thamel, Bhaktapur and Boudha are the core areas for buying thangkas, whereas one can get them at Patan, Swoyambhu and Changu Narayan as well. According to TTA data, 222 thangka galleries function from Kathmandu valley, of which 72 are in Thamel.

Anil informs that the process of making thangka is very tedious. “An artist needs to meditate before starting his piece. Patience and dedication are essential to complete the assignment, which I feel is lacking in the new generation,” he says. Worried about the future of the industry, he suggests the government to include thangka and Buddhist scroll paintings in academia. He adds, “Thangka artists are gradually migrating to foreign lands, which threatens survival of the entire business. The government should carry out concrete work if it wants traditional art to be preserved for future generations.”

Another complaint of thangka artists is the lack of increment in business during ongoing Nepal Tourism Year. “The number of tourists has increased, but since majority of tourists come on special packages, our business has not fostered as we’d hoped,” laments Akka Lama, owner of Tibetan Thanka and School of Thanka Painting at Thamel. According to him, global economic crisis, political instability, and insecurity are main causes for the annual decline in business. However, Lama optimistically says, “The country can benefit from the tourism industry, if the government and concerned professionals concentrate on reducing the challenges and work towards making Nepal a tourist-friendly destination with ample facilities and attractions — one of them being thangka.”

Agreeing with this, Narayan Shrestha, owner of Traditional Art and Handicraft at Patan, says, “Our business relies upon foreigners, so the government should plan well to attract budget tourists.”

He opines that various ministries need to join hands to uplift thangka, tourism, and the nation as a whole.

SUJATA AWALE

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

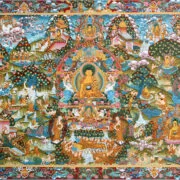

Brief Introduction To Thangka and Mandala Paintings

Thangka (also known as Pauva or Pauba पौभा in Nepali) is a painting usually illustrating a Buddist mandala or a deity. Unlike other painting, a thangka consists of picture painted or embroiled over a cotton cloth and then mounted on a silk frame cover. Although they are delicate in nature, these artworks last a very long time time and retain much of their lustre.

Thangkas served as important teaching and meditating tools. Most of the first artworks depicted the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and the most relevant deities and bodhisattvas.

The most common subject depicted in the entry of Buddhist monasteries is “The Wheel of Life”, which is a diagram depiction of the Abhidharma teachings and the main concepts of Buddhist doctrine.

The paintings of Buddha Life were painted by lamas and monks in monasteries both in Tibet and Nepal. This knowledge was transmitted to members of the monks families and then spread among lay people and devotees that started thangka art painting schools, especially in the Kathmandu valley.

A thangka painting can be considered as an object of decoration, but its spiritual importance is more relevant, especially for Buddhist monks and scholars who revere it with mystic power accordingly to the deities represented.

Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment.

Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities.

History of Thangka in Nepal

Thangka is a Nepalese art form exported to Tibet after Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, daughter of King Lichchavi, married Songtsän Gampo, the ruler of Tibet and thus imported the images of Nepalese deities to Tibet. History of thangka Paintings in Nepal began in 11th century A.D. when Buddhists and Hindus began to make illustration of the deities and natural scenes.

Historically, Tibetan and Chinese influence in Nepalese paintings is quite evident in Thangkas.

It was through Nepal that Mahayana Buddhism was introduced into Tibet during reign of Angshuvarma in the seventh century A.D. There was therefore a great demand for religious icons and Buddhist manuscripts for newly built monasteries throughout Tibet.

A number of Buddhist manuscripts were copied in Kathmandu Valley for these monasteries.

The influence of Nepalese art extended till Tibet and even beyond in China in regular order during the thirteenth century. Nepalese artisans were dispatched to the courts of Chinese emperors at their request to perform their workmanship and impart expert knowledge. The exemplary contribution made by the artisans of Nepal, specially by the Nepalese innovator and architect Araniko, bear testimony to this fact even today.

From the fifteenth century onwards, brighter colours gradually began to appear in Nepalese Thangka. Because of the growing importance of the Tantric cult, various aspects of Shiva and Shakti were painted in conventional poses. Mahakala, Manjushri, White Tara, Chenrezig and other deities were equally popular and so were also frequently represented in Thanka / Thangka paintings of later dates.

As Tantrism embodies the ideas of esoteric power, magic forces, and a great variety of symbols, strong emphasis is laid on the female element and sexuality in the representation of Dakinis and female Goddesses.

Realizing the great demand for religious icons in Tibet, Nepalese artists, along with monks and traders, took with them from Nepal not only metal sculptures but also a number of Buddhist manuscripts. To better fulfill the ever – increasing demand Nepalese artists initiated a new type of religious painting on cloth that could be easily rolled up and carried along with them.

This type of painting became very popular both in Nepal and Tibet and so a new schools of thangka painting evolved as early as the ninth or tenth century and has remained popular to this day.

One of the earliest specimens of Nepalese thangkas dates from the thirteenth century and shows Buddha Amitabha surrounded by Bodhisattva. The Mandala of Vishnu dated 1420 A.D., is another fine example of the painting of this period.

Early Nepalese Thangkas are simple in design and composition. The main deity, a large figure, occupies the central position while surrounded by smaller figures of lesser divinities.

During the reign of Tibetan Dharma King Trisong Duetsen the Tibetan masters refined their already well developed arts through research and studies of different country’s tradition.

Thanka painting’s lining and measurement, costumes, implementations and ornaments are mostly based on Indian styles. The drawing of figures are based on Nepalese style and the background landscapes are based on Chinese style.

Thus, Thangka paintings became a unique and distinctive art.

Thangkas are produced mostly in the northern Himalayan regions among the Newari, Lamas, Gurung and Tamang communities.

Entire families belonging to these communities have preserved this art for generations, which provide today substantial employment opportunities for many people.

How To Order

- Browse our catalog and choose your favorite design.

- Select your preferred size and quality to check the price.

- Click on “Product Inquiry” to send us a message and we will check if we the artwork is immediately available. If not we will make it for you.

- Use the cart page to calculate the shipping cost by selecting your country.

- Once we receive your order we will start creating the artwork according to your preferences and provide you with updates and images upon your request.

We strive to ensure a smooth shopping experience with our assistance. We also welcome commissions of custom designs of thangkas, masks and mandalas.

Shipping and Payments

We offer trusted shipping options to ensure your purchases arrive in perfect condition, and delivered in 5 to 10 working days worldwide. We accept PayPal, debit/credit cards and bank wire transfer services.

About Our Community

We live in Changunarayan, a UNESCO heritage site located on a forested hill overlooking Bhaktapur and the Kathmandu valley. You are welcome to visit our art school and meet our community of artists and artisans.

Learn More About Our Thangka School And Workshops

Goddess Kali Mask

Goddess Kali Mask  Life of Buddha Master Thangka

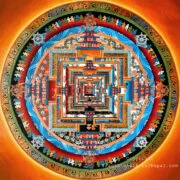

Life of Buddha Master Thangka  Kalachakra Mandala

Kalachakra Mandala  Vajrasattva

Vajrasattva  Vajrabhairava

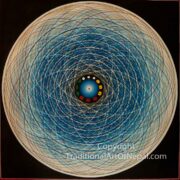

Vajrabhairava  Universe Om Mandala

Universe Om Mandala  Sadhu Baba Masks

Sadhu Baba Masks