Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism

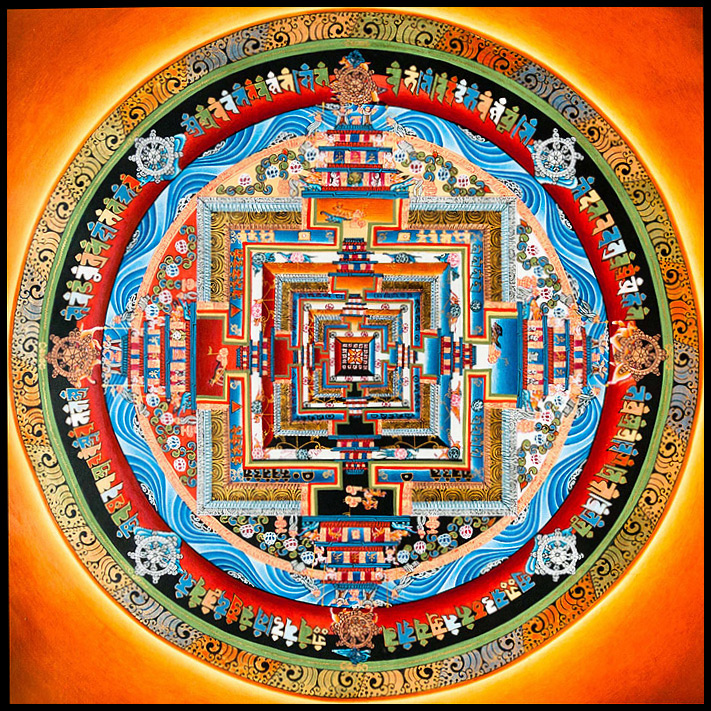

The Sacred Symbolism Of The Kalachakra Mandala

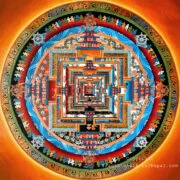

The Kalachakra mandala is definitely one of the most eye-catching thangka painting and appreciated for the symbolic elements that compose it and the visual representation of important teachings of traditional Tibetan Buddhism.

However, as explained by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, many mistaken interpretations have circulated among people who viewed the Kalachakra mandala simply as a work of art.

The Kalacakra tantra is considered the most advanced practice of Vajrayana tradition. This complex system of teachings was originated in India and incorporated into Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

The Dalai Lama himself attends to a series of rituals called “Kalachakra empowerment initiation” and the creation of the Kalachakra mandala is used as a visual textbook for Buddhist practitioners.

The Kalacakra initiation is based on the concepts of time (kala) and cycles (chakra) and, before approaching these rituals, the disciple should have acquired knowledge of the three principal aspects of the Mahayana doctrine: Samsara, Bodhichitta and emptiness.

In this article we will not examine in depth the philosophical aspects of the Tantric initiation but we will focus on explaining the significance of the symbols depicted in the mandala.

First of all it is important to know how to display the Kalachakra mandala correctly. Notice the four different colors of the main inner elements (red, yellow/orange, white and black). The mandala must be oriented with the black side facing down.

The outer ring is called wisdom circle or protective ring. It is decorated with golden flames and the combination of these colors create a rainbow that symbolize the five aspects of the primordial wisdom and the five Dhyani Buddhas.

After the space ring there are four inner rings representing the four main elements: air, fire, water, and earth.

The central part of the mandala had 3 distinct inner layers called body, speech and mind mandalas.

The geometric structure is the projection of a majestic palace with four gates and five floors.

Inside the Body Mandala are represented with syllables and symbols a total of 536 deities. Twelve animals are depicted inside the main gates and protecting the outer walls, representing the months of the year.

The Body Mandala surrounds the Speech Mandala that has the same geometry and inside of which are represented 36 offering goddesses and 80 Yoginis.

The most inner part is called the mind Mandala that occupy the last three floors of the palace and homes 80 deities.

The lotus flower at the center is the symbol of the Buddha mind.

There are several design of thangka paintings of the Kalachakra mandala. In the most complex artworks two deities are depicted in the center of the mandala instead of the lotus flower.

These important deities are Kalachakra and Vishvamata depicted in Yab-Yum: the divine Tantric union that symbolize the cyclic nature of time. This is why the Kalachakra Mandala is also called the “time wheel”.

The Kalachakra Mandala is also represented with one of the most important and well known symbol of the Tibetan Tantric tradition: the Sanskrit seed syllables of the Kalachakra system known as “the mighty ten stacked syllables”.

Each syllable that compose the mantra has a different color and they are represented all interconnected on top of a lotus flower and surrounded by a ring of fire.

To meditate on the mandala and recite the Kalachakra mantra bring peace of mind and benefits for all sentient beings.

The powerful Kalachakra mantra is spelled: Om Ham Ksha Ma La Va Ra Ya Sva Ha.

Namaste.

Brief Introduction To Thangka and Mandala Paintings

Thangka (also known as Pauva or Pauba पौभा in Nepali) is a painting usually illustrating a Buddist mandala or a deity. Unlike other painting, a thangka consists of picture painted or embroiled over a cotton cloth and then mounted on a silk frame cover. Although they are delicate in nature, these artworks last a very long time time and retain much of their lustre.

Thangkas served as important teaching and meditating tools. Most of the first artworks depicted the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and the most relevant deities and bodhisattvas.

The most common subject depicted in the entry of Buddhist monasteries is “The Wheel of Life”, which is a diagram depiction of the Abhidharma teachings and the main concepts of Buddhist doctrine.

The paintings of Buddha Life were painted by lamas and monks in monasteries both in Tibet and Nepal. This knowledge was transmitted to members of the monks families and then spread among lay people and devotees that started thangka art painting schools, especially in the Kathmandu valley.

A thangka painting can be considered as an object of decoration, but its spiritual importance is more relevant, especially for Buddhist monks and scholars who revere it with mystic power accordingly to the deities represented.

Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment.

Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities.

History of Thangka in Nepal

Thangka is a Nepalese art form exported to Tibet after Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, daughter of King Lichchavi, married Songtsän Gampo, the ruler of Tibet and thus imported the images of Nepalese deities to Tibet. History of thangka Paintings in Nepal began in 11th century A.D. when Buddhists and Hindus began to make illustration of the deities and natural scenes.

Historically, Tibetan and Chinese influence in Nepalese paintings is quite evident in Thangkas.

It was through Nepal that Mahayana Buddhism was introduced into Tibet during reign of Angshuvarma in the seventh century A.D. There was therefore a great demand for religious icons and Buddhist manuscripts for newly built monasteries throughout Tibet.

A number of Buddhist manuscripts were copied in Kathmandu Valley for these monasteries.

The influence of Nepalese art extended till Tibet and even beyond in China in regular order during the thirteenth century. Nepalese artisans were dispatched to the courts of Chinese emperors at their request to perform their workmanship and impart expert knowledge. The exemplary contribution made by the artisans of Nepal, specially by the Nepalese innovator and architect Araniko, bear testimony to this fact even today.

From the fifteenth century onwards, brighter colours gradually began to appear in Nepalese Thangka. Because of the growing importance of the Tantric cult, various aspects of Shiva and Shakti were painted in conventional poses. Mahakala, Manjushri, White Tara, Chenrezig and other deities were equally popular and so were also frequently represented in Thanka / Thangka paintings of later dates.

As Tantrism embodies the ideas of esoteric power, magic forces, and a great variety of symbols, strong emphasis is laid on the female element and sexuality in the representation of Dakinis and female Goddesses.

Realizing the great demand for religious icons in Tibet, Nepalese artists, along with monks and traders, took with them from Nepal not only metal sculptures but also a number of Buddhist manuscripts. To better fulfill the ever – increasing demand Nepalese artists initiated a new type of religious painting on cloth that could be easily rolled up and carried along with them.

This type of painting became very popular both in Nepal and Tibet and so a new schools of thangka painting evolved as early as the ninth or tenth century and has remained popular to this day.

One of the earliest specimens of Nepalese thangkas dates from the thirteenth century and shows Buddha Amitabha surrounded by Bodhisattva. The Mandala of Vishnu dated 1420 A.D., is another fine example of the painting of this period.

Early Nepalese Thangkas are simple in design and composition. The main deity, a large figure, occupies the central position while surrounded by smaller figures of lesser divinities.

During the reign of Tibetan Dharma King Trisong Duetsen the Tibetan masters refined their already well developed arts through research and studies of different country’s tradition.

Thanka painting’s lining and measurement, costumes, implementations and ornaments are mostly based on Indian styles. The drawing of figures are based on Nepalese style and the background landscapes are based on Chinese style.

Thus, Thangka paintings became a unique and distinctive art.

Thangkas are produced mostly in the northern Himalayan regions among the Newari, Lamas, Gurung and Tamang communities.

Entire families belonging to these communities have preserved this art for generations, which provide today substantial employment opportunities for many people.

Shoton Festival- Exhibition of Thangkas and Tibetan Masks in Lhasa

The Shoton Festival is held each summer in Lhasa and it is considered to be the largest Tibetan festival. Also known as the Yogurt Banquet festival it dates back to the 11th century and was originally a religious occasion, when local people would offer yogurt to monks who had finished their meditation retreats.

It is a very appealing event not only for Tibetans and Buddhists coming from different countries, but also for many travelers willing to discover this striking event on the roof of the world.

The festival mainly consists in exhibitions showing the art, tradition and the appealing culture of the Tibetan people. Very famous events are the Tibetan Opera Show and the Horsemanship and Yak Race Show. However the main event that open the festival is the display of the giant thangka showing the Great Buddha.

During the ritual more than 100 monks unveil an old 1,480 square-meter portrait of Sakyamuni knitted with colorful silk.

During the festival (this year from the 6th to the 12th of August) there are celebrations in the streets, squares and monasteries of Lhasa.

As part of this year’s festival, a grand exhibition of traditional Thangkas and Tibetan masks is staged at Norbu Lingka, the former summer palace of the Dalai Lamas.

How To Order

- Browse our catalog and choose your favorite design.

- Select your preferred size and quality to check the price.

- Click on “Product Inquiry” to send us a message and we will check if we the artwork is immediately available. If not we will make it for you.

- Use the cart page to calculate the shipping cost by selecting your country.

- Once we receive your order we will start creating the artwork according to your preferences and provide you with updates and images upon your request.

We strive to ensure a smooth shopping experience with our assistance. We also welcome commissions of custom designs of thangkas, masks and mandalas.

Shipping and Payments

We offer trusted shipping options to ensure your purchases arrive in perfect condition, and delivered in 5 to 10 working days worldwide. We accept PayPal, debit/credit cards and bank wire transfer services.

About Our Community

We live in Changunarayan, a UNESCO heritage site located on a forested hill overlooking Bhaktapur and the Kathmandu valley. You are welcome to visit our art school and meet our community of artists and artisans.

Learn More About Our Thangka School And Workshops

Medicine Buddha Paradise

Medicine Buddha Paradise  Five Jambhala Thangka

Five Jambhala Thangka  Citipati Mask

Citipati Mask  Quan Yin Thangka

Quan Yin Thangka  Kalachakra Mandala

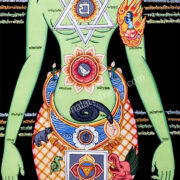

Kalachakra Mandala  Chakraman Yogi

Chakraman Yogi  Vajrabhairava

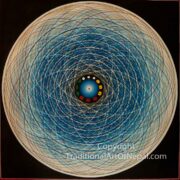

Vajrabhairava  Universe Om Mandala

Universe Om Mandala