Tattoo Artists on Tibetan Thangka Art

It is always rewarding for us to read western artists opinions about the traditional art of thangka paintings.

Thangka Inspired Tattoo

Especially if the artists comes from a background that have such a strong appeal on younger generations as Tattoo art.

Here an interesting article written by Heidi Minx posted on shambhalasun.com

Top tattoo artists talk Tibetan thangka art with Heidi Minx

Having studied art and dharma, and being tattooed for over two decades, my interests collided when I worked on the “Tattoos of Tibetan refugees and ex-political prisoners” project in India last year. Much of the pieces I saw were simple, hand-poked ones that frequently incorporated Bon and Tibetan symbols such as the yundon and dorjee. Here in the West, it’s common for us to see more elaborate, full-color pieces inspired by Buddhas and dharma images by very talented artists from across the ages.

In 2009, I briefly studied the process of thangka with a master in Dharamsala. The training process (a minimum of a five-year full-time commitment), as well as the discipline required, reminded me of the time-honored tradition of tattoo apprenticeships. For example, thangka students must learn the grids and proportional measurements for the three body types: male Buddhas, female Buddhas, and wrathful deities. They must first learn to draw perfectly, often drawing consistently for three years before they are even allowed to touch the paints. They must hand-grind the paints and make canvasses for the senior students — all of this reminded me of tattoo artists learning to clean shop stations properly, drawing, learning how to make needles by hand.

I’ve also learned that tattoo artists themselves often have deep admiration for this style of art, themselves. Here, three big names tell us why in their own words. (Click their names for more information about these artists and to see more of their phenomenal work.)

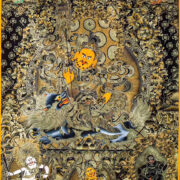

“I’ve been attracted to Tibetan art for a long time. In 93, I traveled through Northern India, Nepal, and Tibet, and purchased quite a few thangkas. They are beautiful and tell such elaborate stories and I know what I feel when I look at them: They seem to be a call to the primal love of god, even if they are not specific to your religion. The details, imagery, layouts — I love them. The fact that the wrathful deities are meant to protect us, it makes perfect sense to me that they be transposed to skin.

“I have tattooed a lot of the imagery over the past 20 years. The contrasting colors and the lines allow them to translate onto the skin so easily. I don’t think in general people are aware of how skilled a painter must be to create these. We can easily find the value of work by, say, Andy Warhol. Several years ago I went to have one of mine appraised. It was a 300-year-old thangka, the appraiser simply told me he didn’t know; it was worth whatever someone would pay for it.”

“Personally, I’ve always been attracted to thangka for the dynamic life/death struggle represented as well as the anthropomoprhic representations of the deities. Thangkhas contain all the elements of mystery that, when I was a young man, fascinated me about the East: strange “alien” text, hallucinogenic geometric designs, shamanistic sacrifice, otherworldly structures. It’s one art form that really has it all.”

“The process of thangka painting seems to parallel tattoo art like no other art-form. Like tattooing, the process is thousands of years old. If done correctly, the paint is hand-mixed with mineral pigments. Artists make their own canvas using natural glues and distemper on 100% cotton. The studying is intense — a minimum of five years. You must draw perfectly first, for 3 years, before you ever touch paint. Your lines must be delicate. You learn to shade with the mineral pigments, and lines must be precise and delicate. The best brushes from Japan are preferred. When it is done correctly, it is fine art.

“That reminds me of tattoos — another ancient art, originally passed on from master to student. The apprentice tattooist learns to make needles, mix colors, cut stencils and draw. The traditional tattoo apprentice must learn to pay close attention to detail and do what his teacher asks him to do. Eventually, the apprentice progresses to tattooing, maybe himself at first. Like thank painting there is a sense of discipline and respect for tradition that, when learned properly, will shine through in the work.

“These are images that tell stories, and aren’t just painted to be pretty artistic expression (although they usually are). Most importantly, they, like the best art, have the power to teach the viewer things about life.”

How To Order

- Browse our catalog and choose your favorite design.

- Select your preferred size and quality to check the price.

- Click on “Product Inquiry” to send us a message and we will check if we the artwork is immediately available. If not we will make it for you.

- Use the cart page to calculate the shipping cost by selecting your country.

- Once we receive your order we will start creating the artwork according to your preferences and provide you with updates and images upon your request.

We strive to ensure a smooth shopping experience with our assistance. We also welcome commissions of custom designs of thangkas, masks and mandalas.

Shipping and Payments

We offer trusted shipping options to ensure your purchases arrive in perfect condition, and delivered in 5 to 10 working days worldwide. We accept PayPal, debit/credit cards and bank wire transfer services.

About Our Community

We live in Changunarayan, a UNESCO heritage site located on a forested hill overlooking Bhaktapur and the Kathmandu valley. You are welcome to visit our art school and meet our community of artists and artisans.

Learn More About Our Thangka School And Workshops

Goddess Kali Mask

Goddess Kali Mask  Five Jambhala Thangka

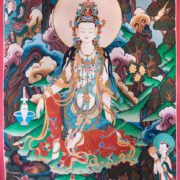

Five Jambhala Thangka  Quan Yin Thangka

Quan Yin Thangka  Vajrasattva

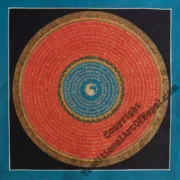

Vajrasattva  Triple Yin-Yang Mandala

Triple Yin-Yang Mandala  Vajrabhairava

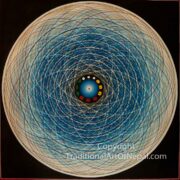

Vajrabhairava  Universe Om Mandala

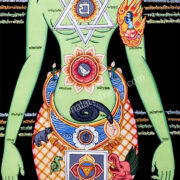

Universe Om Mandala  Chakraman Yogi

Chakraman Yogi

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.