Happiness is an Art

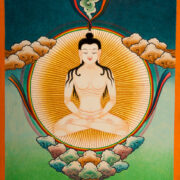

Akasagarbha: The Bodhisattva of Infinite Happiness

“Whether this moment is happy or not depends on you. It’s you that makes the moment happy. It’s not the moment that makes you happy.

With mindfulness, concentration and insight, any moment can become a happy moment.

Happiness is an art.”

Thich Nhat Hanh

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

The Fascinating History of Himalayan Masks

The Origin of Himalayan Masks Cult

Nepalese and Tibetan Masks are one of the symbols that better represent the culture and traditions of people living in the Himalayan region.

The ritual of wearing masks is very old and it comes from animists Himalayan tribes used to worship spirits of nature and guardians of these majestic mountains.

The Shamans of these tribes used to wear masks during rituals they use to perform in order to protect the village, heal diseases, practice exorcisms or other purposes.

Masks supposedly had a very important functions in the social life of these community as they were used also during theatrical representations and ceremonies dedicated to ancestors.

Hindu and Buddhist cultures, that became dominant in the surrounding regions, slowly replaced the myths of this shamanic cult.

However some of the old costumes survived.

Even spirits and demons were adopted by the Buddhist tradition and some of them became wrathful protectors of the Buddhist doctrine.

Padmasambhava and the Rise of Buddhism

Buddhism entered Tibet in the 7th century AD. According to Buddhist mythology the main actor of the transformation of Tibet was Padmasambhava. A famous Tantric Buddhist master from the Swat Valley (today Pakistan) and founder of the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery at Samye, south central Tibet.

Padmasambhava was called by the first Emperor of Tibet to defeat the ancient mountain gods of the old animist cult.

In accordance with the Tantric principle of redirecting negative forces toward spiritual awakening, Padmasambhava converted the wrathful deities, convincing them to become defenders of the new faith.

He is also said to have introduced at Samye Temple the so called Vajra Dance. A dance that takes place in a monastery where masked monks in deep meditation perform rituals that last for three days.

This practice continues today under the name “Cham” and it celebrate Padmasambhava’s conquest over the indigenous cult and their deities.

In Nepal this dance tradition takes a form known as Mani Rimdu: spectacular and colorful masked dances performed during different religious festival.

Iconography of Tibetan Masks

Considering the polytheist nature of both Hindu and Buddhist traditions the deities represented by Tibetan masks are numerous: Shiva, Bhairava, Ganesh, Mahakala, Garuda and Varahi are the most famous.

Some of the deities are depicted using animals like the Lion associated with Sima or the Tiger symbolizing Duma.

However the images must follow the rules and prescriptions described in old manuals and iconographic books.

There are several books that set those guidelines, one of the earliest is from the first half of the 15th century. All the masks display a common element: the open third eye mark on the forehead.

The style of Tibetan and Nepalese Masks is characterized by elaborate pointed crowns with skulls, various head-bands, earrings and many other colorful elements.

These decorations not only reflect religious and symbolic aspects but also add a powerful imagery and a peculiar and fascinating look.

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

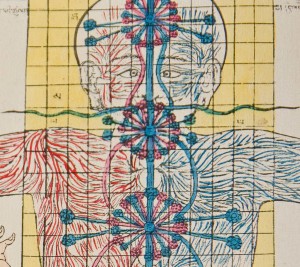

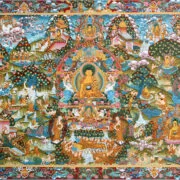

The Thangkas of The Tibetan Medicine

Created between 1687 and 1703, these thangka paintings were commissioned by the fifth Dalai Lama’s regent, Desi Sangye Gyatso, who stepped in as interim ruler of Tibet after the Dalai Lama died in 1682.

The paintings constitute the charts of The Blue Beryl, a text written by Gyatso as commentary of the Four Tantras, the fundamental text of Tibetan medicine.

The main reason that moved Gyatso to create this illustrations was to avoid confusion when interpreting old texts.

Gyatso placed great value on the accuracy of the illustrations depicting such things as the use of omens and dreams for making diagnoses, hundreds of medicinal herbs and medical instruments, and fabulous diagrams of human anatomy.

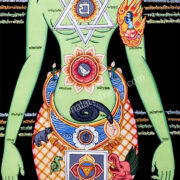

As stated by the International Academy for Traditional Tibetan Medicine (IATTM) “one of the unique features of Traditional Tibetan Medicine is that it contains a comprehensive philosophy, cosmology, and system of subtle anatomy with associated spiritual practices”.

Today these Thangkas constitute a fundamental piece of educational art that interweave Tibetan Buddhist traditions with centuries-old medical knowledge.

The first painting occupies a privileged place among the others which, in a certain sense, derive from it. It represents the celestial city of the Buddha Bhaisajyaguru, Master of Remedies “Surdasana”. The city is surrounded by four “mountains”. Further more it is square with the palace at its center. The palace, like the whole locality, is an emanation of Buddha Bhaisajyaguru. Its plan evokes a Mandala, with its square enclosure and its four gates oriented in the cardinal directions.

The thangkas not only depict the Buddhist background of Tibetan medicine but also the diagnostic schemes of pulse and urine analysis, picturesque representations of dietary and behavioral advice for treating illnesses, as well as anatomical knowledge,charts for moxabustion, and the elaborate “materia medica” of Tibetan pharmacology.

In fact Twenty-one Thangkas of the original series are devoted to more large human figures illustrating anatomical structures.

The first fifteen compositions have a top register. The registers contain the four main sequential topics relating to the origin myths and state narrative on the Tibetan History of Medicine of the late 17th century.

There are four main sequential topics contained in the registers:

– Medicine Buddha and early Indian Gods and Rishis.

– The Lineage of the Four Medical Tantras.

– The Yutog Nyingtig Lineage.

– The Deities and Protectors of the Yutog Nyingtig.

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

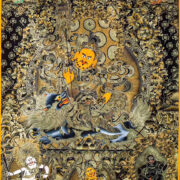

Raktayamari Thangka: A Closer Look at the Thangka Worth $45 Million

Overlook

Widely recognised as one of the most important Asian works of art and one of the world’s great textile treasures, this Thangka was recently bought for $45 million.

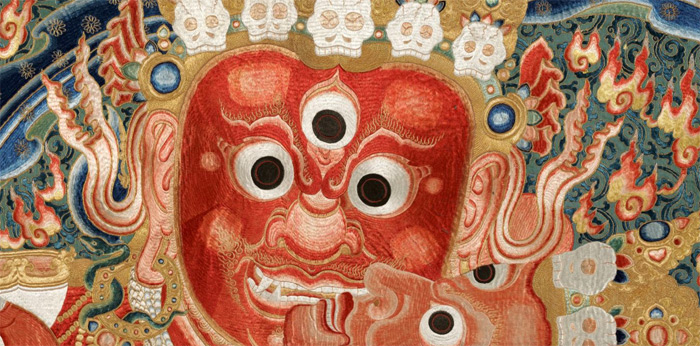

The Thangka depicts the majestic Raktayamari, the red Conqueror of Death, standing in yab-yum embracing his consort, Vajravetali.

Raktayamari is an important deity of Anuttarayoga-Tantra in Vajrayana Buddhism, and one of the three Yamari forms of Bodhisattva Manjusri (the other two being Vajrabhairava and Krishna-Yamari) revered by various Tibetan sects.

The highlights on the torsos and limbs of Raktayamari and Vajravetali, to denote the musculature, are some of the most common motifs in Nepalese-Tibetan paintings and a notable characteristic of figures in classical Tibetan art.

Highlights and Symbolism

Every aspect of the form of Yamari and the consort Vajra Vetali have symbolic and coded meaning.

The red body color represents the desire to overcome all sufferings and place all beings in the state of enlightenment. The weapon that Raktayamari holds subdues the afflictions (maras).

The left hand holds a cup made by ancient Lama’s skull and containing the essence of the four maras transformed.

The three round eyes express compassion for all beings in the three times of past, present and future as well as the three watches of the day and three watches of the night.

The orange and red hair is to symbolize the increasing qualities of the Buddha and the aspects of the Mahayana Five Paths.

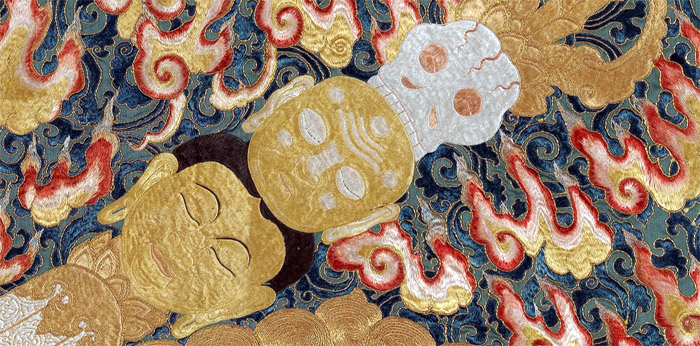

The crown of five dry skulls symbolizes the five poisons transformed into the five wisdoms.

The necklace of fifty fresh heads represents the vowels and consonants of the Sanskrit language.

The eight snakes represent the subjugation of various obstacles and the accomplishment of skillful activities.

The locked couple is trampling on the blue corpse of Yama, the Lord of death, wearing a tiger skin and crown, lying on the back of their mount, a brown buffalo recumbent on a multi-coloured lotus base.

All below two rows of buddhas and bodhisattvas seated on lotus bases, the upper including Heruka Vajrabhairava on the far left and Manjusri on the far right, flanking the five Dhyani Buddhas.

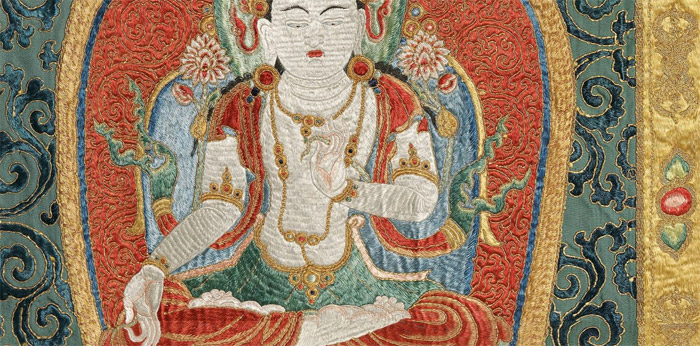

Below this row of deities are two Taras – Green Tara on the left, and White Tara on the right.

In the lower panel is a row of seven offering goddesses dancing on lotus bases and holding aloft dishes as offerings below the couple.

Meaning of the artwork

The metaphor for Rakta Yamari is ‘death.’ The name means the ‘Red Killer of Death.’

In this symbolic meaning the idea of death refers directly to the suffering and unhappiness in the world as described in Buddhist philosophy.

The general appearance of the deity, number of faces, arms, ornaments, decorations and attributes are all part of a mnemonic device (memory system) that incorporates the most essential of Buddhist principles and core teachings into a single object.

The one face represents the embodiment of the wisdom of all Buddhas as having one taste, or flavor, ultimate truth. The red body color represents the desire to overcome all “maras” and place all beings in the state of enlightenment.

Bibilography

Henss, Michael. ‘The Woven Image: Tibeto-Chinese Textile Thangkas of the Yuan and Early Ming Dynatsies’, Orientations, November 1997.

Himalayan Art Resources. Rakta Yamari Main Page. http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=349. Jeff Watt, 2-2005.

Himalayan Art Resources. Rakta Yamari Textile. HAR no. 57041. http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/57041.html.

Raktayamari-tantraraja-nama. Gshin rje’i gshed dmar po zhes bya ba’i rgyud kyi rgyal po [TBRC w25383, w25384].

Reynolds, Valrae, ‘Buddhist Silk Textiles: Evidence for Patronage and Ritual Practice in China and Tibet.’ Orientations, April 1997.

George Roerich (trans.), Biography of Dharmasvamin, A Tibetan Monk Pilgrim. Patna: K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute, 1959.

George Roerich (trans.), The Blue Annals. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1996, 2nd ed.

Follow traditionalartofnepal.com on WordPress.com

How To Order

- Browse our catalog and choose your favorite design.

- Select your preferred size and quality to check the price.

- Click on “Product Inquiry” to send us a message and we will check if we the artwork is immediately available. If not we will make it for you.

- Use the cart page to calculate the shipping cost by selecting your country.

- Once we receive your order we will start creating the artwork according to your preferences and provide you with updates and images upon your request.

We strive to ensure a smooth shopping experience with our assistance. We also welcome commissions of custom designs of thangkas, masks and mandalas.

Shipping and Payments

We offer trusted shipping options to ensure your purchases arrive in perfect condition, and delivered in 5 to 10 working days worldwide. We accept PayPal, debit/credit cards and bank wire transfer services.

About Our Community

We live in Changunarayan, a UNESCO heritage site located on a forested hill overlooking Bhaktapur and the Kathmandu valley. You are welcome to visit our art school and meet our community of artists and artisans.

Learn More About Our Thangka School And Workshops

Five Jambhala Thangka

Five Jambhala Thangka  Life of Buddha Master Thangka

Life of Buddha Master Thangka  Tapihritsa Bon Yogi

Tapihritsa Bon Yogi  Red Mahakala Mask

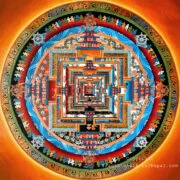

Red Mahakala Mask  Kalachakra Mandala

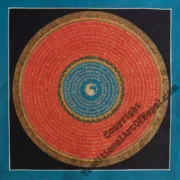

Kalachakra Mandala  Triple Yin-Yang Mandala

Triple Yin-Yang Mandala  Sadhu Baba Masks

Sadhu Baba Masks  Chakraman Yogi

Chakraman Yogi